In 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art agreed to buy three photographs by Diane Diane (pronounced “Dee-ANN,” after the French heroine in a play her mother liked) Arbus, for seventy-five dollars each. Wiser counsels prevailed, however, and a few months later the museum decided to take only two. Why splurge? The Museum of Modern Art was more daring; in 1964, it had acquired seven Arbus photos, including “Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C.” Like so many artists, Arbus found real fame only after her death. Public fascination started to seethe, swelling far beyond the bounds of her profession. A 1972 monograph of her work became one of the best-selling photography books of all time.

The swell has never slowed, and prices have followed suit. At Christie’s, in 2007, “Child with a toy hand grenade” sold for two hundred and twenty-nine thousand dollars. Last year, another print of it, this one signed by the artist, fetched seven hundred and eighty-five thousand dollars. That’s quite a hike.

One coup, in Arthur Lubow’s new biography, “Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer,” is an interview with Colin Wood, [the child with the toy hand grenade] conducted by Lubow in 2012. We learn that Wood was a Park Avenue kid, stranded at the time with nannies while his parents were busy divorcing, and “living primarily on powdered Junket straight from the box.” He brought his toy guns to school. Wood says of Arbus, “She saw in me the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid wanting to explode but can’t because he’s constrained by his background.” If she did see all that, it was by instinct, with a touch of fellow-feeling; she had started out much like Colin, and continued that way.

[Her favorite subjects were the invisible, even if they were cute kids; the shunned, the aged, the pitiable, those of indeterminate gender. Those who we secretly feared.–Esco]

|

|

Yes,. you guessed right. Gloria Vanderbilt’s son, Anderson Cooper. |

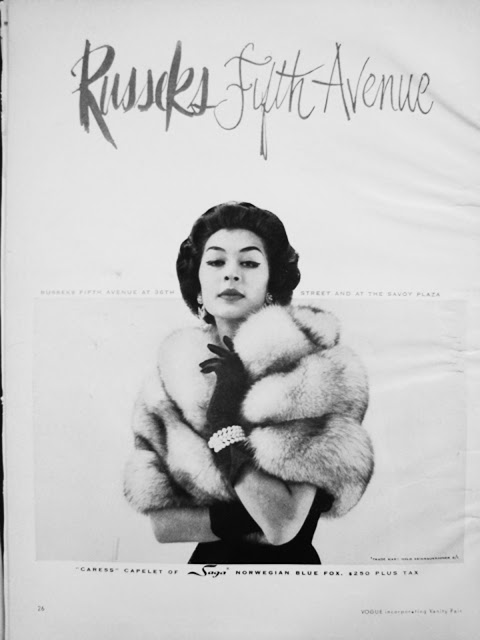

She was a Russek, which to anyone who suddenly needed a mink stole, in the depths of the Great Depression, was a name to reach for. Russeks, founded by her maternal grandfather, was originally a furrier’s; by 1924, it was a department store on Fifth Avenue, selling not only furs but also gowns, coats, and, as an advertisement put it that year, “smart accessories for the correctly dressed woman.” In 1919, Diane’s mother, Gertrude, married a young window dresser at the store named David Nemerov. Their son, Howard, who grew up to become poet laureate, was born twenty-one weeks after the wedding. Diane was born in 1923, and her sister, Renee, in 1928.

They raised their three children on Park Avenue and then in a 14-room apartment in the San Remo on the Upper West Side; She was cared for by a bevy of nannies and maids, driven by a chauffeur, cooked for by a professional.

|

|

Brenda Frazier, pictured in 1966, twenty-eight years after she had been crowned “débutante of the year.” She appears to be held together by powder, paint, and pearls. |

———————–

Gertrude, according to Lubow, “typically stayed in bed in the morning past eleven o’clock, smoking cigarettes, talking on the telephone, and applying cold cream and cosmetics to her face.” At one point, she fell into a ravine of depression and got stuck, sitting wordlessly at the family dinner table. She had suffered a nervous breakdown that left her unable to wash or dress for many months, while the children were cared for by the help. .“I stopped functioning. I was like a zombie,” she recalled later.

Her husband, meanwhile,… smooth and frictionless, rose through the ranks of Russeks as if stepping into the elevator. By 1947, he had arrived at the position of president.

During this period, 11-year-old Diane locked herself in her bedroom for hours at a time.

Arbus did not endure her suffering alone, for her brother, Howard, was close to her. Both were precocious students, and they shared other talents, too. Diane masturbated in the bathroom with the blinds up, to insure that people across the street could watch her, and as an adult she sat next to the patrons of porno cinemas, in the dark, and gave them a helping hand. (This charitable deed was observed by a friend, Buck Henry, the screenwriter of “The Graduate.”) Not to be outdone in these vigorous stakes was her brother, who later, in a book called “Journal of the Fictive Life,” defined his self-abuse as “worship.” He added, “My father once caught me at it, and said he would kill me if it ever happened again.” A friend of Gertrude’s once told Howard that reading Freud would make you sick. On the contrary, it would be like a day in the life of the Nemerovs.

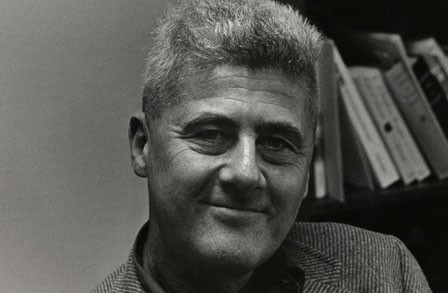

The summit of this weirdness comes before Lubow has reached page twenty, with the disclosure, from Arbus, that “the sexual relationship with Howard that began in adolescence had never ended. She said that she last went to bed with him when he visited New York in July 1971. That was only a couple of weeks before her death.” The source for this is psychiatrist Helen Boigon, who treated Arbus in the last two years of her life, and who was interviewed—though not named—by Patricia Bosworth for her 1984 biography of Arbus. (The results are in an archive at Boston University.) William Todd Schultz, too, communicated with Boigon for “An Emergency in Slow Motion” (2011), his unblushing psychological portrait of Arbus. …The intimate rapport of brother and sister was apparently recounted to the psychiatrist in a casual manner, as though incest were no big deal—just a family habit that you kept up, like charades.

|

|

Howard Nemerov |

And that otherworldly coolness drifts into Arbus’s art. What her admirers respond to is not so much the gallery of grotesques as her reluctance to be wowed or cowed by them, still less to censure them or to set them up for mockery. If she was a pilgrim on the fringes of society, it was fascination rather than compassion that drove her there, and many of the outcasts she discovered, far from being ground down, had elected to cast themselves out. The balding and shirtless figure who glares at us in “Tattooed man at a carnival, Md.” (1970) requests not an atom of our pity. Indeed, he puts our undistinguished bodies to scorn, brandishing the art work of his torso as thou

gh to holler, “Get a load of me.”

When Diane Nemerov was thirteen, she fell in love with Allan Arbus, who worked in the advertising department at Russeks .[They married] and Allan [gave] his wife a camera after their honeymoon, and she [took] a course with the photographer Berenice Abbott, at the New School. When the war ended, Allan and Diane, with the encouragement (and the financial assistance) of David Nemerov, went into business together.

|

|

Diane and Allan Arbus |

NEW YORK

Diane, growing up on Central Park West; Allan, the city-college dropout five years her senior, working a menial job in the shop’s ad department. The pair transformed themselves into a duo of fashion photographers, shooting for magazines from Vogue to Glamour to Harper’s Bazaar for nearly a decade…. . After long hours in the studio, she’d hurry home to cook dinner for her husband and their two young daughters, Doon and Amy

If they were not completely monogamous — why be so bourgeois? — they were completely committed to each other.

But Diane was growing dissatisfied. She dreamt up the concepts for their shoots — then spent her days handling the models, pinning their clothes in place, a role even Allan admitted was “demeaning.” Besides, she’d begun asking herself, what could she possibly learn by posing a person in borrowed clothes, inserting them as a human fill-in-the-blank into some art director’s fantasy?

Diane committed herself to wandering New York City with her 35mm Nikon, following strangers down the street or lying in wait in doorways until she saw someone she felt compelled to photograph. This was the onset of a lifelong addiction to experience, which would feed her and consume her in equal measure.

The exhibit at the Met Breuer, “diane arbus: in the beginning,” features about 70 never-before-seen prints, [covering] the experiments that immediately followed.

Allan helped find her a studio and darkroom, continued taking on commercial work under their joint name, and made sure their assistant developed her rolls before any of his magazine materials. “The most important work that goes on here,” he’d say, “is Diane’s.”

Her first move was to study with Lisette Model, who steered her away from the hazy (“I used to make very grainy things,” Arbus recalled) and toward a clarity that would specify rather than blur—confronting us with this person, in this place, wearing this outfit, or no outfit at all.

One day I said to her, and I think this was very crucial. I said, “Originality means coming from the source, not like [Harper’s Bazaar Art Director Alexey] Brodovitch–‘at any price to be different…’ And from there on, Diane was sitting there and–I’ve never in my life seen anybody–not listening to me but suddenly listening to herself through what was said.” [authors’ italics. Lisette Model, in an interview with Doon Arbus, Revelations, 2003, first paperback ed p.141 ]

For Arbus, the advice was heaven-sent. It gave her permission to be the artist she was ready to be.