|

Swing Landscape (1938)

|

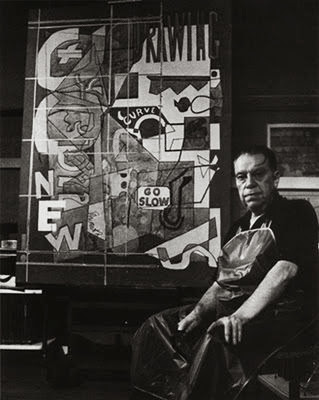

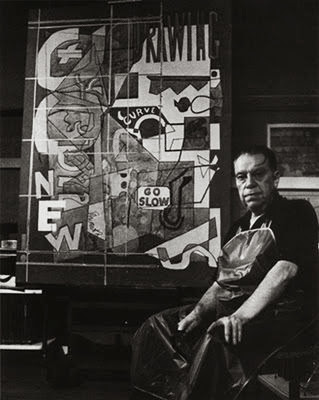

Stuart Davis is best known, and rightly esteemed, for his later, tightly composed, hyperactive, flag-bright pictures, with crisp planes and emphatic lines, loops, and curlicues, often featuring gnomic words (“champion,” “pad,” “else”) and almost always incorporating his signature as a dashing pictorial element. Their musical rhythms and buttery textures appeal at a glance. If the works had a smell, it would be like that of a factory-fresh car—an echt American aura, from the country’s post-Second World War epoch of dazzling manufacture and soaring optimism. But, in this beautifully paced show, hung by the Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, Davis’s earlier phases prove most absorbing. They detail stages of a personal ambition in step with large ideals….Newness in art held precedence for Davis in all weather, and, like other leftist painters of the time, he adopted the belief that artistic progress is somehow inherently revolutionary.

|

Percolator” (1927).

|

|

Egg Beater No. 1

1927

|

|

Egg Beater No. 4” (1928)

|

Beginning in 1921, collage-like paintings of tobacco packages, light bulbs, and a mouthwash bottle wrestle with Cubism in what amounts to proto-Pop art. Four “Egg Beater” paintings, from 1927 and 1928, memorialize a concerted effort to transcend Cubism, and even to challenge Picasso, with rigorous variations on a tabletop array of household objects. The thirteen months that Davis spent in Paris, starting in 1928, yielded flattened, potently charming cityscapes in toothsome colors.

|

“Place Pasdeloup” (1928).

|

|

Report from Rockport, 1940

|

Back home, he fed his semi-abstracting campaign with motifs from summer sojourns in Gloucester, Massachusetts: signs, boat riggings, gas pumps. His sporadic output in the thirties ran to murals. The rioting shapes and hues of the more than fourteen-foot-long “Swing Landscape” (1938), made for a government-funded housing project in Brooklyn, leap beyond the compositional order—contained and balanced—of French predecessors, chiefly Fernand Léger. They jostle outward, anticipating the “all-over” principle that Jackson Pollock realized, with his drip paintings, a decade later.

|

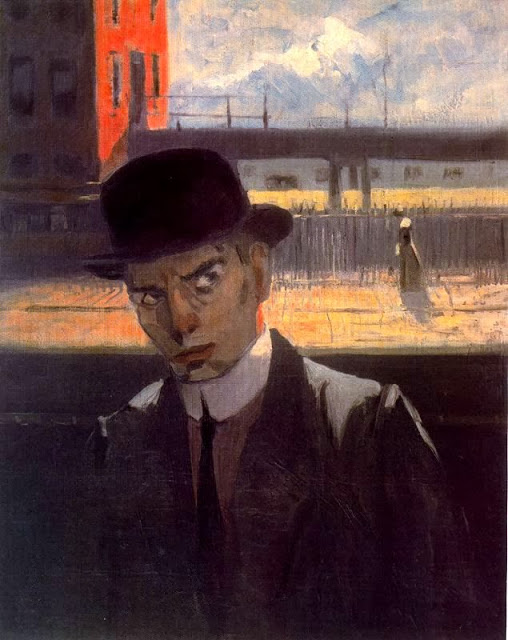

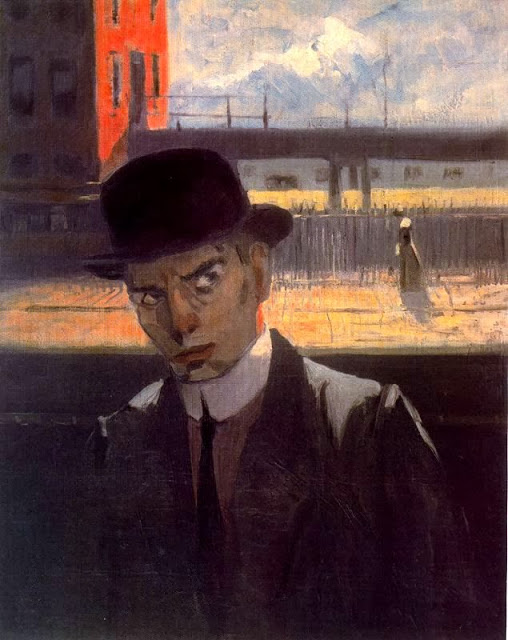

Self-Portrait 1912

|

|

Davis was born in 1892 in Philadelphia, the first child of artists who had studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. His father, Ed, working as a newspaper illustrator, became involved with the budding Ashcan-school illustrators-turned-painters, led by the charismatic Robert Henri. (A star of that cohort, John Sloan, became an early mentor and lifelong friend of Stuart’s.) The family moved to East Orange, New Jersey, in 1901, as Ed bounced between jobs. Stuart, at sixteen, persuaded his parents to let him quit high school and enroll in Henri’s art school, in Manhattan. He also began frequenting bars in Newark and Hoboken, where he commenced his habits as a prodigious drinker and a passionate jazz buff. As he later recalled, “You could hear the blues, or Tin Pan Alley tunes turned into real music, for the cost of a five-cent beer.” In 1910, after less than half a year of formal study, he showed realist work, with other members of the Henri circle. Two years later, he was illustrating for the socialist magazine The Masses. He had five watercolors in the 1913 Armory Show, which was, he later told a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, “the greatest single influence I have experienced.”

|

New York Mural 1932

|

Around that time, New York’s modernizing art world, small as it was, developed factions. The most sophisticated was that of the group that formed around Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, founded in 1905, which showed the European new masters and emphasized photography. More eclectic was the Whitney Studio Club, established in Greenwich Village in 1918 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Davis gravitated to the latter, which took on painters from the disbanded Henri school and whose most talented member was Edward Hopper. A stipend from Whitney and her director, Juliana Force, rescued Davis from poverty in the nineteen-twenties, and Whitney’s purchase of two of his paintings funded his trip to Paris.

He was devastated when, in 1932, his first wife, Bessie Chosak, died after a botched abortion. But, within weeks, he was at work on a chipper mural for the men’s lounge at Radio City Music Hall.

Seeing no contradiction between patriotism and radical politics, throughout the nineteen-thirties Davis all but set aside studio work, dismissing leftist demands for proletarian themes in art, to engage in labor-organizing activism.

|

Artists Against War and Fascism 1936

|

In the forties, Davis’s drinking reached a crisis level, which sharply reduced his productivity but still had no evident effect on his style. A painting that was key to the evolution of his late period, “The Mellow Pad,” begun in 1945, remained upbeat even though it took him six years to complete. Sobriety, following a collapse of his health in 1949, launched him on his prolific last phase, which accounts for more than half of the work in the Whitney show. His joyous art finally became authentic to a life of worldly success and domestic contentment with his second wife, Roselle Springer.

|

The Mellow Pad, (1945-1951)

|

For those who, like me, are longstanding and unwavering fans of Davis’s work, the current show at the Whitney, “Stuart Davis: In Full Swing”—put together by Barbara Haskell, that institution’s resident expert in prewar modernism and Harry Cooper, curator of modern art at the National Gallery of Art, where the show will travel in November—is a welcome occasion to re-experience his bracing achievement….the exhibition is a carefully conceived and expertly realized introduction Davis’s electrifying contribution.

|

Odel 1924

|

|

Visa (1951)

|

|

“Lucky Strike” (1921).

|

The “spontaneity” of Davis’s paintings was as meticulously prepared and rehearsed as a Coleman Hawkins saxophone solo. The decade-wide parentheses in dating of Ultramarine (1942-1952) and American Painting (1932/1942-1954)—both almost mosaics of eccentrically cropped chromatic fragments—testify to the protracted gestation of works that look as if they’d been speedily and effortlessly knocked out.

|

American Painting (1932/1942-1954)

|

Davis was a man so imbued with the lust for life that he was incapable of producing dull or depressing art and plainly would have never understood how art as a deliberate denial of pleasure, could be “good for the cause”—any cause. From his breakthrough in the mid-1920s until his death at seventy-one in 1964, just as the wave of Pop artists—to whom he gave courage and taught ways of seeing and doing—crested, Davis concentrated single-mindedly on making art quiver with the energy he perceived around him. Jazz was an inherently urban music, but in Davis’s art its pulse could be felt everywhere, from Hudson River docks to small seaport towns in New England where swing bands and bebop combos—not to mention African-Americans—were few and far between.

|

Ultra Marine 1943

|

Seeing this Davis retrospective against the background of terrible events in the world at large and agonizing violence and divisiveness at home, [it exemplifies] how sustaining great art is even in the grimmest of times.

|

Owh! in San Pao” (1951).

|

Well done.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike