|

|

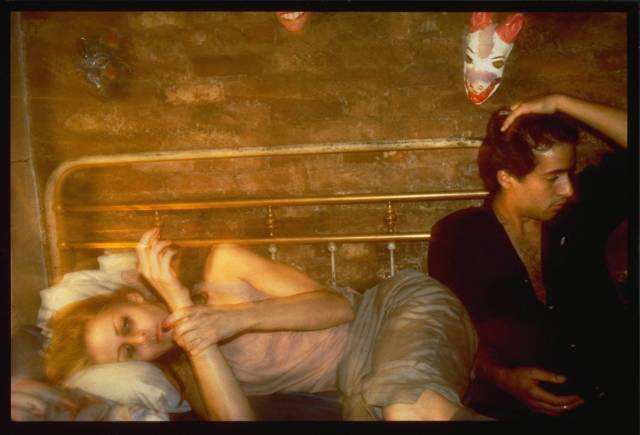

“Trixie on the Ladder, NYC” (1979): Goldin “showed life as it was happening.”PHOTOGRAPH BY NAN GOLDIN / |

HILTON ALS, NEW YORKER

Just as certain works of literature can radically alter our understanding of language and form, there are a select number of books that can transform our sense of what makes a photograph, and why. Between 1972 and 1992, the Aperture Foundation published three seminal photography books, all by women. “Diane Arbus” (1972), published a year after the photographer’s death, documented a world of hitherto unrecorded people—carnival figures and everyday folk—who lived, it seemed, somewhere between the natural world and the supernatural. Sally Mann’s “Immediate Family” (1992), a collection of carefully composed images of Mann’s three young children being children—wetting the bed, swimming, squinting through an eyelid swollen by a bug bite—came out when the controversy surrounding Robert Mapplethorpe’s “The Perfect Moment” exhibition was still fresh, and it reopened the question of what the limits should be when it comes to making art that can be considered emotionally pornographic.

Nestled between these two projects was Nan Goldin’s “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” (1986). (An exhibition of the slide show and photographs from which the book was drawn opened this month, at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York.) “The Ballad” was Goldin’s first book and remains her best known, a benchmark for photographers who believe, as she does, in the narrative of the self, the private and public exhibition we call “being.” In the hundred and twenty-seven images that make up the volume proper, we watch as relationships between men and women, men and men, women and women, and women and themselves play out in bedrooms, bars, pensiones, bordellos, automobiles, and beaches in Provincetown, Boston, New York, Berlin, and Mexico—the places where Goldin, who left home at fourteen, lived as she recorded her life and the lives of her friends.

What interests Goldin is the random gestures and colors of the universe of sex and dreams, longing and breakups—the electric reds and pinks, deep blacks and blues that are integral to “The Ballad” ’s operatic sweep. In a 1996 interview, Goldin said of snapshots, “People take them out of love, and they take them to remember—people, places, and times. They’re about creating a history by recording a history. And that’s exactly what my work is about.”

Goldin’s parents, Hyman and Lillian, grew up poor. They “were intellectual Jews, so they didn’t care about money,” she told me. “Most of all, my father cared about Harvard. He attended the university at a time when there was a kind of quota on Jews. It was a very small quota. Going to Harvard was the biggest thing in his life.” Hyman and Lillian met in Boston and married on September 1, 1939, the day Germany invaded Poland. Hyman went to work in the economics division of the Federal Communications Commission. Nancy was born, the youngest of four children, in 1953, and grew up, first, in the suburb of Silver Spring, Maryland, a quiet, orderly place, where, Goldin has said, the main goal was not to reveal too much or pry into the well-manicured lives of your neighbors. As a girl, she longed to know what was behind those closed doors. She also longed to escape that world of convention, she told me, in her high-ceilinged, top-floor apartment in a Brooklyn brownstone—which she moved into, in part, because it’s O.K. to smoke there, an eighties vice that she has carried into the new millennium. (Goldin also lives in Berlin; she left the U.S. in 2000, when George W. Bush was elected.)

Her older brother Stephen, a psychiatrist who now lives in Sweden, was one of her first protectors, she said, but it was her older sister, Barbara, who claimed her emotional attention. Barbara confided in her and played music for her and had all the makings of an artist herself…. “There was a lot of bickering going on, and I wished they’d get divorced most of my childhood.”…. Barbara acted out and could not be controlled—she was, according to Stephen, often violent at home, breaking windows and throwing knives—and her parents had her committed to mental hospitals, on and off, for six years. …“Barbara said, ‘All I want to do is go home.’ She was fifteen. And my mother said, ‘If she comes home, I’m leaving.’ And my father just sat there with his head down….The one good shrink I’ve had says I survived because, by the age of four, my friends were more important to me than my family,”

“I was eleven when my sister committed suicide.”

I was very close to my sister and aware of some of the forces that led her to choose suicide. I saw the role that her sexuality and its repression played in her destruction. Because of the times, the early sixties, women who were angry and sexual were frightening, outside the range of acceptable behavior, beyond control. By the time she was eighteen, she saw that her only way to get out was to lie down on the tracks of the commuter train outside of Washington, D.C. It was an act of immense will.

In the week of mourning that followed, I was seduced by an older man. During this period of greatest pain and loss, I was simultaneously awakened to intense sexual excitement. In spite of the guilt I suffered, I was obsessed by my desire.

From the introduction to “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.”

By the time Goldin was thirteen, she was reading The East Village Other, listening to the Velvet Underground, and aspiring to become a junkie, a “slum goddess,” a bad girl free of the limiting roles with which so many women define their social self—daughter, wife, mother. At fourteen, after being kicked out of a number of boarding schools “for smoking pot or some bullshit,” Goldin left home. For a time, she lived in communes and foster homes.

|

|

Suzanne with Mona Lisa, Mexico City” (1981).© NAN GOLDIN / |

“I met Nan when she was fourteen,” the performer Suzanne Fletcher told me. “She was in a foster home in Massachusetts. I was aware of her because she was so cool.” The two became close friends the following year, when Goldin enrolled in the Satya Community School, where Fletcher was a student. ….There Goldin met David Armstrong, a gay fellow-student who eventually became a photographer, too, and was Goldin’s closest male friend for decades. (He died, of liver cancer, in 2014.) The two were involved, from the first, in a kind of mariage blanc. They went to movies all the time, were fascinated by the women of Andy Warhol’s Factory, and in love with thirties stars like Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. “We were really radical little kids, and we did cling to our friendships as an alternative family,” Fletcher told me. “Even at the time, we could have articulated that.”

Goldin became the school photographer and found her voice, both through the camera, she says now, and through Armstrong, who taught her that humor could be a survival mechanism. She became able to joke and laugh; before that, she said, she barely spoke above a whisper. (Goldin also told me that, for her, the camera was a seductive tool, a way of becoming socialized.) Fletcher remembers Goldin’s “passion to document”: “She kept journals, then the photography became a visual journal,” recording the lives of her friends. (Fletcher is one of the most memorable subjects in “The Ballad.” )

By the time Goldin was eighteen, she was living in Boston with a much older man…. Eventually, she fell in with a group of drag queens, who hung out in a bar called the Other Side, and began to photograph them. She wanted to memorialize the queens, get them on the cover of Vogue. She had no interest in trying to show who they were under the feathers and the fantasy: she was in love with the bravery of their self-creation, their otherness.

Goldin never had any real truck with camera culture—the predominantly straight-male world of photography in the sixties and seventies, when dudes stood around talking about apertures and stroking their tripods, in an effort to butch up that sissy job, otherwise known as “making art.” She took a few courses at the New England School of Photography, but was less engaged by the technical instruction than by a class taught by the photographer Henry Horenstein, who recognized the originality of her work. He turned her on to Larry Clark, who had photographed teen-agers having sex and shooting up in sixties Tulsa. The intimacy of Clark’s pictures—you can almost smell the musk—inspired Goldin. Here were noncommercial images that promoted not glamour but lawless bohemianism, or just lawlessness.

In 1974, she enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, in Boston, where she studied alongside Armstrong, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and Mark Morrisroe—photographers driven by their color fantasies of relationship drama and alienated youth.

In the summer of 1976, Goldin rented a house with Armstrong and his lover in Provincetown, where she met the writer and actress Cookie Mueller, who appeared in a number of John Waters’s films, and whom she photographed extensively. In her 1991 book, “Cookie Mueller,” Goldin writes:

She was a cross between Tobacco Road and a Hollywood B-Girl, the most fabulous woman I’d ever seen. . . . That summer I kept meeting her at the bars, at parties and at barbecues with her family—her girlfriend Sharon, her son Max, and her dog Beauty. Part of how we got close was through me photographing her—the photos were intimate and then we were.

(Mueller died, of aids, in 1989.)

|

|

Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City” (1983).© NAN GOLDIN |

At the end of that Provincetown summer, Goldin had image after image of her friends in the dunes, partying, living their lives as if they had all the time in the world.

|

|

Nan Goldin and Marvin Heiferman |

The curator Marvin Heiferman was working in New York then, at Castelli Graphics, a business run by the art dealer Leo Castelli’s wife, Antoinette. While Leo dealt with artists like Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg in then funky SoHo, Antoinette helped push graphics and photographs—which weren’t always considered “real” art—in a stuffy Upper East Side town house. One day, Heiferman got a call from a young woman who said that the photographer Joel Meyerowitz had referred her. Heiferman told her that he wasn’t looking at new work, but the voice on the phone was insistent. “Then this person shows up in a blue polka-dot dress with a whole lot of crinolines and wacky hair and a box under her arm,” Heiferman recalled. “She shows me this box of pictures, and they’re really weird and curiously made, with a very strange color sense about them, and they were of everything from people smoking cigarettes to fucking. There were probably twenty to twenty-five pictures. And I had never seen anything like that, in terms of their density and their connection with the people in them.” Heiferman told Goldin to bring more work the next time she came. A few months later, she arrived with a wooden crate full of photographs. “Again, I’m thinking, This is extraordinary work, right? I loved them and wanted to show them, but Mrs. Castelli thought they were too raw. She worried that they would upset people, that Ellsworth Kelly wouldn’t like them.”

Although Heiferman eventually included Goldin in a group show, it was almost a decade before she got her due as an artist. There’s an unspoken rule in photography, not to mention in art in general, that women are not supposed to be, technically speaking, voyeurs—they’re supposed to be what voyeurs look at.

“ ‘The Ballad’ was a brilliant solution for someone who shoots like her,” Heiferman said. “It showed life as it was happening, and she wound up with something that was an amalgam of diaristic and family pictures and fashion photography and anthropology and celebrity photography and news photography and photojournalism. And nobody had done that before.

|

|

“Nan on Brian’s Lap, Nan’s Birthday, New York City” (1981).© NAN GOLDIN |

Goldin was tending bar at Tin Pan Alley, an “Iceman Cometh” type of watering hole on West Forty-ninth Street, when she met an office worker and ex-marine named Brian, a lonesome Manhattan cowboy with a crooked-toothed smile, who eventually fell into acting. Goldin ended their first date by asking him to cop heroin for her in Harlem. He did. Drugs consumed them, as did their physical attraction to each other. In “The Ballad,” we see Brian sitting on the edge of Goldin’s bed, smoking a cigarette, or staring at the camera with lust, certainly, but wariness, too, his hairy chest a sort of costume of masculinity.

|

|

Nan and Brian in Bed, New York City” (1983).© NAN GOLDIN |

[Writer and friend Darryl] Pinckney describes Goldin’s lover as “tall but uncertain.” He adds, “His only asset seemed to be that he was a man, but it was his physical advantage as a man that allowed him to convert into a weapon his sense of entitlement and injury, his resentment at being the backstage husband.” In 1984, the couple were in Berlin, and, Goldin told me, “Brian was dope-sick. We were staying at a pensione, and he started beating me, and he went for my eyes, and later they had to stitch my eye back up, because it was about to fall out of the socket. He burned my journals, and the sick thing was that there were people around who knew us and who wouldn’t help me. He wrote ‘Jewish-American Princess’ in lipstick on the mirror.”

Goldin made it back to the U.S., where Fletcher helped get her to a hospital so that her eye could be saved. While recovering, she made a self-portrait, “Nan one month after being battered” (1984), which is, perhaps, the most harrowing image in “The Ballad.” We see Goldin’s blackened eyes and swollen nose and, in a stroke of pure genius, her red-lipsticked lips. It’s the tender femininity of those lips that brings the horror into focus.

|

|

“Nan One Month After Being Battered” (1984).© NAN GOLDIN |